In another question, 18 percent of participants stated that their attitude towards the use of SRM had changed for the better since the Paris Climate Agreement. However, twice as many say they have become even more sceptical over the past ten years.

Those who now have a more positive attitude towards geoengineering cite rising CO₂ concentrations in the atmosphere or approaching tipping points for coral reefs, for example, as the main reasons for this. The increase in extreme events and the accelerated warming of the oceans have caused them to rethink their position, explained a climate researcher from the South Pacific; she now supports the use of marine cloud brightening.

Overall, however, comments on the survey are dominated by criticism of solar radiation modification. Many researchers fear that countries act unilaterally and that the effects of such interventions, for example on biodiversity or the water cycle, are unknown. ‘Geoengineering approaches are a fig leaf that serves to avoid taking action by promising “something” for the future,’ writes a climate researcher from northern Germany.

1,800 launches into the stratosphere per day

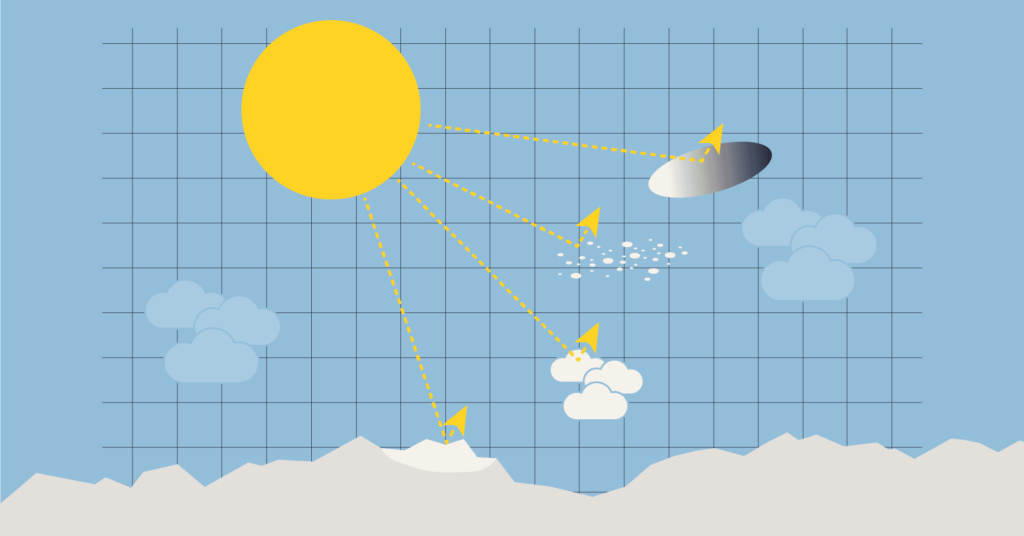

The British Royal Society recently compiled the current state of research. According to this, most of the findings on both aerosol release and marine cloud brightening come from computer-based climate models. Nevertheless, there is ‘reliable evidence that a globally coordinated use of SRM could reduce the global mean surface temperature and associated effects such as sea level rise, forest fires and extreme precipitation, thereby masking part of the anthropogenic climate change’.

The Royal Society estimates that 1,800 aircraft would have to take off every day to cool the world by one degree Celsius with sulphur particles. This amount is challenging, but technically possible: 650 aircraft take off every day from London Heathrow Airport alone. Since the particles are best distributed high up in the atmosphere, the planes would have to climb to at least eight kilometres, and even more than 20 kilometres over the tropics because the atmosphere bulges around the equator. ‘The sky would be a little less blue as a result,’ said climate researcher James Haywood at the presentation of the Royal Society study, but not as dimmed as it would be after a volcanic eruption.

According to estimates, marine cloud brightening with the same cooling effect would require around 27,000 jets spraying salt water into the atmosphere around the clock, each at a rate of around 100 litres per minute.

Would the monsoon suddenly fail to arrive in India? No one knows

However, even in the stratosphere, aerosols lose their effect after two years at the latest, while greenhouse gases such as CO₂ can heat the atmosphere for centuries. This means that geoengineering would probably have to be carried out for decades or even centuries. If artificial cooling ends, warming rises again abruptly, which is known as ‘termination shock’.